I may have done a "happy dance" when I found Sharon Kay Penman's novel for $2 in a thrift shop. I'd known about it for several years and been even more eager to read it after the announcement of the discovery of Richard III's remains in February. However, I expected it might take me longer than the library would allow to finish this 936 page novel. I was wrong; it took me just over two weeks, and that with rereading several portions. And the "happy dance" was just the first of many physical reactions that this sweeping epic provoked from me.

I guess I should confess straight off. I'd been holding out on taking the final plunge, joining the rabid Ricardian ranks - declaring Richard III my liege lord. My alleged reason, if I had to give one, would have been that while it certainly can't be proved that Richard was responsible for the death of the Princes in the Tower, he did have enough motivation. The real reason is that while I've had plenty of historical crushes in my lifetime, Ricardians are embarrassingly numerous, organized, and earnest. However, my historical interests have always been in the biographical, "how did individuals live and feel?" aspects, not dispassionate political analysis. (Or rather, I'm interested in reading that analysis after I've developed an emotional attachment to characters, which then makes me too biased to ever be a historian.) I'm susceptible to hagiography, as shown by how much I loved Penman's version of Richard. By the final hundred pages I was in tears, pounding my bed, whimpering, and softly damning consumption, the Stanleys and Henry Tudor.

Why? Because Penman portrays Richard as a prince among men. That's not because his brother is a king, but because in comparison to the intemperate, impious, self-serving men around him, Richard is a model of virtue and justice. He is loyal to a fault and utterly uxorious to Anne Neville. (Yes, I realize the latter is not a very historically valid interpretation.) From the beginning pages with Richard as the sensitive six-year-old, to the final (slightly overlong) final chapters on early Tudor propaganda, it's unabashed hagiography. Penman tries, but can afford virtually no sympathy for Richard's foes, from Elizabeth Woodville to Henry Tudor. And, yes, Richard is a romantic hero; we don't just respect him, we fall in love with him. Or at least I did. Maybe I should resent that, but I don't.

Since I recently read Philippa Gregory's Cousins War novels, comparisons were inevitable. I certainly felt like I entered into the emotions and motivations of the characters more in this novel than in Gregory's. While Gregory's novels focus on the women behind the famous men, I still felt like several women got their due more from Penman. (Cecily Neville isn't so blatantly biased as in Gregory's account where she favors George, Duke of Clarence, despite his betrayals of his brothers and slander of her own name. Nan Neville's relationship with her daughter Anne is still strained, but not so utterly hostile as in The Kingmaker's Daughter. However, in the latter Gregory has a complex - if slightly confusing - portrayal of Anne and Isabel Neville's relationship that this novel lacks.) While the medieval issues of witchcraft and magic cannot be denied, I've found Gregory's repetitious emphasis on this theme slightly annoying. In contrast, Penman gives a limited, but respectful, view of Catholic faith in those times.

My biggest complaint about the novel is actually its grammar. While the substitution of "be" for "are" could be argued to lend historic sense to necessarily-modern speech patterns, the dropping of conjunctions in the narrative portions brought me up short rather frequently.

My emotional absorption in the novel hasn't entirely beclouded my vision. I still acknowledge that within the morality of his time Richard III is neither black nor white. I am, however, with Jane Austen, "rather inclined to suppose him a very respectable man" and Henry Tudor "as great a villain as ever lived."

Also, I'm nerdy enough that I'm including this graphic of the Battle of Barnet (found here) for future reference.

There is no frigate like a book

There is no frigate like a bookTo take us lands away,

Nor any coursers like a page

Of prancing poetry.

~ Emily Dickinson

Literature is my Utopia. Here I am not disenfranchised. No barrier of the senses shuts me out from the sweet, gracious discourses of my book friends. They talk to me without embarrassment or awkwardness. ~ Helen Keller

Friday, 17 May 2013

Thursday, 2 May 2013

The Best of Lord Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane

Perhaps that title is a little unfair since I have not (yet) read all the Wimsey novels. However, I believe it is a truth universally acknowledged that Gaudy Night is the best of Sayer's oeuvre, and the other novels featuring Harriet Vane are also greatly esteemed among her readers.

Have His Carcase

I thoroughly enjoyed getting to know Harriet Vane and Lord Peter better. One of the things I especially liked about this novel is that Lord Peter doesn't do everything by himself. Indeed, Harriet is making suggestions and discoveries along with him the entire time. The novel is most notable as a precursor to Gaudy Night, showing Harriet's unwillingness to have an unequal relationship with Peter based on gratitude. As with previous Sayers mysteries, I finished it in (nearly) a day.

Gaudy Night

Gaudy Night is a hard book to categorize: is it merely a mystery? an intelligent romance? a campus novel? a feminist bildungsroman? It contains multiple complex themes - such as balancing head and heart, intellectual integrity, and women's education - yet manages to sustain an entertaining central story. In this respect it reminds me a little of Middlemarch. Actually that connection is hardly surprising since I first learned of Gaudy Night from a friend who kindly sent me a term essay she'd written comparing female intellectuality in the two novels. I've been waiting to read it for almost three years now and it certainly didn't disappoint. Rather, it was a slightly dangerous read, making me fall more in love with a place, a (fictional) person, and a profession.

Besides intelligence and complexity, Gaudy Night shares with Middlemarch an abundance of literary epigraphs that add to the novel's intellectual, and even academic, air. One of my goals is to eventually be able to read all the French and Latin passages without looking up or guessing meanings.

Busman's Honeymoon

How do you describe perfection? While this novel has its humorous vignettes, and while it's also a romance novel, it's ultimately gravely serious. It's serious about the things in life that really matter. One of these things is maintaining integrity and independence in relationships. It's a heady blend of honesty about the difficulty of marriage (such as the moment when Peter and the Superintendent are having a little too much fun at the expense of the suspected Miss Twitterton and Harriet feels the two men are "on the far side of a chasm, and she hated them both") and passion bathed in the fiercely intelligent light of John Donne. It's obvious that Sayers poured the depths of her intelligence and conscience into this novel when we see Peter's struggles with his persona as the wealthy, hobbyist sleuth whose work condemns people to death.

Yes, all the Donne poetry the two quote to each other is a significant factor in my love for this novel. Ironically, there aren't really words to describe it. For me personally, Donne is about grace that strengthens the intellect, and vice versa. This novel presents the intellectuality of Donne's poetry as elevating and purifying the erotic.

Here's a review that explains how Sayers created such lasting works through breaking all the mystery writers' rules.

Now that I've read the best novels, I confess I'm hesitant to go back and read the other three I own (Murder Must Advertise, Nine Tailors, and Five Red Herrings) that don't feature Harriet. I'm more likely to reread the above novels, or even go for some of Sayers' theological or academic works.

A Few Favorite Quotes ("A few!" Excuse me while I type out half the books.)

The following is one of those passages I had encountered before reading the novel. Susan Wise Bauer further whetted my appetite for this novel, writing of the "great golden phrases".

Are you noticing a theme in page numbers? This is the "still centre" where the plot of the novel pauses. And yet it's the most evocative, memorable part. After that the plot seems to pick up again with sufficient speed that I ceased to add exclamations and stars in the margins, so you, reader, are spared a dozen more quotes. Now to Busman's Honeymoon.

From the diary of the endlessly quotable Dowager Duchess of Denver:

(That last phrase "as Kirk would say" is a reference to the game of filling conversation up with literary quotes that Peter and Harriet play with a police inspector. Peter's tendency to "talk piffle" tempts me to start throwing Shakespeare, Donne, and Browning into random conversations.)

Well, I can't capture the charm, the vigor, the honesty of these books in a few quotes. What searching for my favorite passages to share has taught me is that I need to reread these novels. Soon.

Have His Carcase

I thoroughly enjoyed getting to know Harriet Vane and Lord Peter better. One of the things I especially liked about this novel is that Lord Peter doesn't do everything by himself. Indeed, Harriet is making suggestions and discoveries along with him the entire time. The novel is most notable as a precursor to Gaudy Night, showing Harriet's unwillingness to have an unequal relationship with Peter based on gratitude. As with previous Sayers mysteries, I finished it in (nearly) a day.

Gaudy Night

Gaudy Night is a hard book to categorize: is it merely a mystery? an intelligent romance? a campus novel? a feminist bildungsroman? It contains multiple complex themes - such as balancing head and heart, intellectual integrity, and women's education - yet manages to sustain an entertaining central story. In this respect it reminds me a little of Middlemarch. Actually that connection is hardly surprising since I first learned of Gaudy Night from a friend who kindly sent me a term essay she'd written comparing female intellectuality in the two novels. I've been waiting to read it for almost three years now and it certainly didn't disappoint. Rather, it was a slightly dangerous read, making me fall more in love with a place, a (fictional) person, and a profession.

Besides intelligence and complexity, Gaudy Night shares with Middlemarch an abundance of literary epigraphs that add to the novel's intellectual, and even academic, air. One of my goals is to eventually be able to read all the French and Latin passages without looking up or guessing meanings.

Busman's Honeymoon

How do you describe perfection? While this novel has its humorous vignettes, and while it's also a romance novel, it's ultimately gravely serious. It's serious about the things in life that really matter. One of these things is maintaining integrity and independence in relationships. It's a heady blend of honesty about the difficulty of marriage (such as the moment when Peter and the Superintendent are having a little too much fun at the expense of the suspected Miss Twitterton and Harriet feels the two men are "on the far side of a chasm, and she hated them both") and passion bathed in the fiercely intelligent light of John Donne. It's obvious that Sayers poured the depths of her intelligence and conscience into this novel when we see Peter's struggles with his persona as the wealthy, hobbyist sleuth whose work condemns people to death.

Yes, all the Donne poetry the two quote to each other is a significant factor in my love for this novel. Ironically, there aren't really words to describe it. For me personally, Donne is about grace that strengthens the intellect, and vice versa. This novel presents the intellectuality of Donne's poetry as elevating and purifying the erotic.

Here's a review that explains how Sayers created such lasting works through breaking all the mystery writers' rules.

Now that I've read the best novels, I confess I'm hesitant to go back and read the other three I own (Murder Must Advertise, Nine Tailors, and Five Red Herrings) that don't feature Harriet. I'm more likely to reread the above novels, or even go for some of Sayers' theological or academic works.

A Few Favorite Quotes ("A few!" Excuse me while I type out half the books.)

She had written what she felt herself called upon to write; and, though she was beginning to feel that she might perhaps do this thing better, she had no doubt that the thing itself was the right thing for her. It had overmastered her without her knowledge or notice, and that was the proof of its mastery.Gaudy Night, p43

Not one man in ten thousand would say to the woman he loved, or to any woman: 'Disagreeableness and danger will not turn you back, and God forbid they should.' That was an admission of equality, and she had not expected it of him. If he conceived of marriage along those lines, then the whole problem would have to be reviewed in that new light; but that seemed scarcely possible. To take such a line and stick to it, he would have to be, not a man but a miracle.Ibid, 262

The following is one of those passages I had encountered before reading the novel. Susan Wise Bauer further whetted my appetite for this novel, writing of the "great golden phrases".

In that melodious silence, something came back to her that had lain dumb and dead ever since the old, innocent undergraduate days. The singing voice, stifled long ago by the pressure of the struggle for existence, and throttled into dumbness by that queer, unhappy contact with physical passion, began to stammer a few uncertain notes. Great golden phrases, rising from nothing and leading to nothing, swam up out of her dreaming mind like the huge, sluggish carp in the cool water of Mercury.... Then, with many false starts and blank feet, returning and filling and erasing painfully as she went, she began to write again, knowing with a deep inner certainty that somehow, after long and bitter wandering, she was once more in her own place.Ibid, 268,269

Meanwhile she had got her mood on to paper - and this is the release that all writers, even the feeblest, seek for as men seek for love; and, having found it, they doze off happily into dreams and trouble their heads no further.Ibid, 270

Are you noticing a theme in page numbers? This is the "still centre" where the plot of the novel pauses. And yet it's the most evocative, memorable part. After that the plot seems to pick up again with sufficient speed that I ceased to add exclamations and stars in the margins, so you, reader, are spared a dozen more quotes. Now to Busman's Honeymoon.

From the diary of the endlessly quotable Dowager Duchess of Denver:

Busman's Honeymoon p. 19Wonder whether Mussolini's mother spanked him too much or too little - you never know, these psychological days.

Peter: How can I find words? Poets have taken them all, and left me with nothing to say or do--

Harriet: Except to teach me for the first time what they meant.Ibid, 326

For God's sake let's take the word "possess" and put a brick round its neck and drown it. I will not use it or hear it used - not even in the crudest physical sense. It's meaningless. We can't possess one another. We can only give and hazard all we have - Shakespeare, as Kirk would say...Ibid, 362

(That last phrase "as Kirk would say" is a reference to the game of filling conversation up with literary quotes that Peter and Harriet play with a police inspector. Peter's tendency to "talk piffle" tempts me to start throwing Shakespeare, Donne, and Browning into random conversations.)

Well, I can't capture the charm, the vigor, the honesty of these books in a few quotes. What searching for my favorite passages to share has taught me is that I need to reread these novels. Soon.

Wednesday, 1 May 2013

March and April Reading Roundup

Currently reading: The Sunne in Splendour by Sharon Kay Penman (thrilling $1 find at a thrift shop) and The Darwin Conspiracy by John Darnton (random selection at library). Listening to Heretic Queen: Elizabeth I and the Wars of Religion by Susan Ronald (seemed an appropriate selection for April, since last year at this time I immersed myself in Elizabeth's world).

Warning: Since I missed posting last month, this is a loooong post. Reviews of novels by authors I've read multiple books by lately are separate. I want to start writing more detailed reviews directly after finishing books, so subsequent Monthly Reading Roundups may contain links to longer reviews.

Young Romantics by Daisy Hay

Daisy Hay's stated aim in this group-biography is to dispel the myth of the second generation Romantic poets (especially Shelley, Byron, and Keats) as a solitary geniuses, and to illuminate the "mingled yarn" of their interactions and friendships. As such, it gives a comprehensive biography of many figures, as well as amusing anecdotes of their shared creativity. However, as the their lives and communities unravel (with the tragic deaths of Keats and Shelley) the story is poignantly sad. Not least because Hay is not writing hagiography: no one is wholly sympathetic. In fact, in the words of Mary (Godwin) Shelley's step-sister Claire Clairmont, Shelley and Byron's philosophy of free love transformed them into "monsters of lying, meanness, cruelty and treachery." Certainly I found Byron deplorable in his behavior to Claire and their daughter Allegra. (Basically, I hate him.) Shelley frequently showed himself unsympathetic to the anguish endured by Mary after the deaths of three children. Much to my surprise I found myself liking Leigh Hunt best of the assembled (male) caste, although Hay is honest about his financial inabilities that gave rise to Dickens' caricature of him in the character of Harold Skimpole. Keats drifted in and out of the group and he was the notable poet I felt the book explored least.

Since I'm not particularly familiar with the second-generation Romantics, this group biography of them was a good introduction

Imprison Him by Miriam Wood

The story of an Adventist pastor/missionary/administrator imprisoned for six months by the totalitarian government of an unnamed (due to danger for others) African country. I still really want to know which country this is, as I'm sure it had legitimate grievances with imperialism that it reacted to dangerously. A good account of a wife's loyalty and the emotional and spiritual struggles of the persecuted. It's been sitting on my grandma's bookshelf my whole life, so I'm thankful I finally read it, but it's definitely not among the most memorable reads of the year.

Mightier than the Sword: Uncle Tom's Cabin and the Battle for America by David S. Reynolds

Weird. I thought I'd written a short goodreads review of this, but now don't see one. However, I've written quite a lengthy post inspired by this book - so far my favorite non-fiction read of the year.

Escape from Camp 14 by Blaine Harden

I've read a shelf of books with "escape" in the title. From stories of Jews under Nazism, to Christians under Communism, to Huguenots under Catholicism, I've learned about torture, hard-labor, and how the human spirit sustains courage and compassion in the worst circumstances. Shin In Geun's story is different: born into North Korea's worst internment camp, he never knew a time when he was valuable. He viewed his mother as a competitor for food, and felt no qualms of conscience when he reported that he had heard her and his brother planning to escape. Watching them executed as a result of his snitching, he felt only resentment against the parents who had caused him to be born into this hideous prison. Years later, as his conscience developed in the Western world, he developed remorse and self-loathing for the "memory of the kind of son he once was." This, for me, was probably the most tragic part of the book: the dehumanization of the camp system and then the torture experienced when individuals come to understand the guilt of the past.

North Korea is "viewed by human rights groups as the world's largest prison", and Camp 14 is said to be among the worst of its many prison camps. It is a place where Shin had his finger cut off for dropping a piece of machinery, a place where a little girl may be beaten to death for stealing a few kernels of corn. The book points out that even "free" North Korean escapees are malnourished and under-sized for their age. It ultimately raises the question of why powerful governments are willing to allow such human rights atrocities to continue and also what we as individuals can do to increase awareness and concern.

Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller

I tend to identify and empathize with failed, fatally flawed, characters, so of course was heart-broken by Willy Loman's doomed attempt to grasp and hold the American Dream. My one notable complaint about this play is that it failed the Bechdel Test.

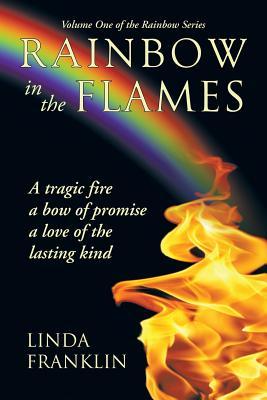

Rainbow in the Flames: A Tragic Fire, A Bow of Promise, A Love of the Lasting Kind by Linda Franklin

Linda and eight-year-old Jed were alone at their remote mountain home when an explosion left him with third degree burns over more than half of his body. The story follows their painful journey of months spent in hospitals, years spent getting grafts, decades of regrets and questions. The most poignant and touching moments for me were reading of the despair and patience exhibited in one tiny little person. This book was also good for me because it taught me to see the humanity in people I disagree with. I know of the Franklins through their ministry (Sanctuary Ranch) and through mutual acquaintances. I've read one of Mr. Franklin's books, and disagree very strongly with his views on courtship, marriage roles, and women's dress and hair. However, this book showed me the pained, loving, and human hearts that lie behind the ideas and images of the people I am so quick to judge. Thus the book was both a rebuke and a beautiful inspiration.

Though the Heavens Fall by Mikhail P. Kulakov Sr.

Elder Kulakov became the leader of the Euro-Asian Division of Seventh-day Adventists and a translator of a Russian New Testament. But years before that he spent 5 years in a hard labor camp for his Christian faith and witnessing. Even after being released he experienced the constant surveillance that Stalin's regime exercised toward Christians. My mom and I read this together over a several months, so the story is already a little hazy in my memory. However, one vignette told Pastor Kulakov by a fellow prisoner stood out in my mind as similar to the world of 1984. It concerned a speech at a District Party Meeting that was loudly applauded, with a standing ovation, by all present. "For three minutes, four minutes, five minutes... it continued... Palms were getting sore and raised arms were already aching. The older people were panting from exhaustion." Yet all were afraid that stopping would brand them as enemies of the Party. Finally, "after eleven minutes, the director of the paper factory assumed a businesslike expression and sat down in his seat.... That same night [he] was arrested. They easily pasted 10 years on him on the pretext of something quite different. After he signed... the final document of the interrogation, his interrogator reminded him: 'Don't ever be the first to stop applauding!'" (p. 63-64)

Links to reviews of three Dorothy Sayers mysteries and three Philippa Gregory historical fiction novels.

(All images from goodreads.com)

Warning: Since I missed posting last month, this is a loooong post. Reviews of novels by authors I've read multiple books by lately are separate. I want to start writing more detailed reviews directly after finishing books, so subsequent Monthly Reading Roundups may contain links to longer reviews.

Young Romantics by Daisy Hay

Daisy Hay's stated aim in this group-biography is to dispel the myth of the second generation Romantic poets (especially Shelley, Byron, and Keats) as a solitary geniuses, and to illuminate the "mingled yarn" of their interactions and friendships. As such, it gives a comprehensive biography of many figures, as well as amusing anecdotes of their shared creativity. However, as the their lives and communities unravel (with the tragic deaths of Keats and Shelley) the story is poignantly sad. Not least because Hay is not writing hagiography: no one is wholly sympathetic. In fact, in the words of Mary (Godwin) Shelley's step-sister Claire Clairmont, Shelley and Byron's philosophy of free love transformed them into "monsters of lying, meanness, cruelty and treachery." Certainly I found Byron deplorable in his behavior to Claire and their daughter Allegra. (Basically, I hate him.) Shelley frequently showed himself unsympathetic to the anguish endured by Mary after the deaths of three children. Much to my surprise I found myself liking Leigh Hunt best of the assembled (male) caste, although Hay is honest about his financial inabilities that gave rise to Dickens' caricature of him in the character of Harold Skimpole. Keats drifted in and out of the group and he was the notable poet I felt the book explored least.

Since I'm not particularly familiar with the second-generation Romantics, this group biography of them was a good introduction

Imprison Him by Miriam Wood

The story of an Adventist pastor/missionary/administrator imprisoned for six months by the totalitarian government of an unnamed (due to danger for others) African country. I still really want to know which country this is, as I'm sure it had legitimate grievances with imperialism that it reacted to dangerously. A good account of a wife's loyalty and the emotional and spiritual struggles of the persecuted. It's been sitting on my grandma's bookshelf my whole life, so I'm thankful I finally read it, but it's definitely not among the most memorable reads of the year.

Mightier than the Sword: Uncle Tom's Cabin and the Battle for America by David S. Reynolds

Weird. I thought I'd written a short goodreads review of this, but now don't see one. However, I've written quite a lengthy post inspired by this book - so far my favorite non-fiction read of the year.

Escape from Camp 14 by Blaine Harden

I've read a shelf of books with "escape" in the title. From stories of Jews under Nazism, to Christians under Communism, to Huguenots under Catholicism, I've learned about torture, hard-labor, and how the human spirit sustains courage and compassion in the worst circumstances. Shin In Geun's story is different: born into North Korea's worst internment camp, he never knew a time when he was valuable. He viewed his mother as a competitor for food, and felt no qualms of conscience when he reported that he had heard her and his brother planning to escape. Watching them executed as a result of his snitching, he felt only resentment against the parents who had caused him to be born into this hideous prison. Years later, as his conscience developed in the Western world, he developed remorse and self-loathing for the "memory of the kind of son he once was." This, for me, was probably the most tragic part of the book: the dehumanization of the camp system and then the torture experienced when individuals come to understand the guilt of the past.

North Korea is "viewed by human rights groups as the world's largest prison", and Camp 14 is said to be among the worst of its many prison camps. It is a place where Shin had his finger cut off for dropping a piece of machinery, a place where a little girl may be beaten to death for stealing a few kernels of corn. The book points out that even "free" North Korean escapees are malnourished and under-sized for their age. It ultimately raises the question of why powerful governments are willing to allow such human rights atrocities to continue and also what we as individuals can do to increase awareness and concern.

Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller

I tend to identify and empathize with failed, fatally flawed, characters, so of course was heart-broken by Willy Loman's doomed attempt to grasp and hold the American Dream. My one notable complaint about this play is that it failed the Bechdel Test.

Rainbow in the Flames: A Tragic Fire, A Bow of Promise, A Love of the Lasting Kind by Linda Franklin

Linda and eight-year-old Jed were alone at their remote mountain home when an explosion left him with third degree burns over more than half of his body. The story follows their painful journey of months spent in hospitals, years spent getting grafts, decades of regrets and questions. The most poignant and touching moments for me were reading of the despair and patience exhibited in one tiny little person. This book was also good for me because it taught me to see the humanity in people I disagree with. I know of the Franklins through their ministry (Sanctuary Ranch) and through mutual acquaintances. I've read one of Mr. Franklin's books, and disagree very strongly with his views on courtship, marriage roles, and women's dress and hair. However, this book showed me the pained, loving, and human hearts that lie behind the ideas and images of the people I am so quick to judge. Thus the book was both a rebuke and a beautiful inspiration.

Though the Heavens Fall by Mikhail P. Kulakov Sr.

Elder Kulakov became the leader of the Euro-Asian Division of Seventh-day Adventists and a translator of a Russian New Testament. But years before that he spent 5 years in a hard labor camp for his Christian faith and witnessing. Even after being released he experienced the constant surveillance that Stalin's regime exercised toward Christians. My mom and I read this together over a several months, so the story is already a little hazy in my memory. However, one vignette told Pastor Kulakov by a fellow prisoner stood out in my mind as similar to the world of 1984. It concerned a speech at a District Party Meeting that was loudly applauded, with a standing ovation, by all present. "For three minutes, four minutes, five minutes... it continued... Palms were getting sore and raised arms were already aching. The older people were panting from exhaustion." Yet all were afraid that stopping would brand them as enemies of the Party. Finally, "after eleven minutes, the director of the paper factory assumed a businesslike expression and sat down in his seat.... That same night [he] was arrested. They easily pasted 10 years on him on the pretext of something quite different. After he signed... the final document of the interrogation, his interrogator reminded him: 'Don't ever be the first to stop applauding!'" (p. 63-64)

Links to reviews of three Dorothy Sayers mysteries and three Philippa Gregory historical fiction novels.

(All images from goodreads.com)

Philippa Gregory's Cousins' War Novels

The following are some thoughts on the novels in Philippa Gregory's Cousin's War series that I've read (or listened to as audiobooks) in recent months.

The White Queen

I first listened to this novel (about Elizabeth Woodville, queen consort of Edward IV) as an abridged audiobook early in the year and was disappointed. The abridged version showed little of the York court, concentrating on Elizabeth's times in sanctuary during the wars and Lancastrian restoration. It also expunged references to Edward's unfaithfulness, a thing that would have doubtless been sometimes on Elizabeth's mind, even if she tolerated it. However, skimming through the hardback book, I found that these elements were indeed there. I still wouldn't call it a favorite; I didn't connect with the portrayal of Elizabeth's personality. That said, Gregory should be commended for writing a decently sympathetic portrait of the woman who was - and in historical fiction (such as The Sunne in Splendour) still seems to be - the reviled Wallis Simpson of her age. As with her novel about Elizabeth's mother, Jacquetta of Luxembourg, Gregory portrays women as using forbidden herbalism and magic to gain their own form of power in a man's world.

The Red Queen

The extreme piety and sense of purpose that makes many readers dislike Gregory's characterization of Margaret Beaufort (grandmother of Henry VIII) at first enlisted my sympathy, reminding me of Dorothea Brooke in my beloved Middlemarch. However, eventually Margaret's self-centered outlook, and a rather slow-moving plot, turned me off. I only finished it to find out Gregory's unusual theory on the fate of the Princes in the Tower

The Kingmaker's Daughter

This novel - centering on the life of Anne Neville, queen consort of Richard III - was rather uneven. It had some wonderful moments showing the absolute horror and danger of childbirth in late Medieval times. Anne's relationship with her sister Isabel was depicted as close and complex. However, I never really felt like Anne's character was well defined. Especially confusing was how quickly she became loyal to her formerly-feared mother-in-law, Margaret d'Angou. Richard (yes, of course that's who we're really interested in) is quite well-drawn. Gregory doesn't come across as a raving Ricardian or a Shakespearean hater. Her Richard can be kind or ruthless, simultaneously charismatic and calculating.

While Gregory isn't a very highbrow author, I probably will pick up the other books in the series when I see them at the library. Of course I'm already raising my eyebrows at the premise of her new book on Princess Elizabeth of York. SPOILERS FOLLOW which appears to be that Elizabeth and Richard III were lovers. It is, of course, not an unprecedented idea and it's hardly surprising that it was the route Gregory chose to take. She is certainly never one to miss out on the most sensational interpretation.

The White Queen

I first listened to this novel (about Elizabeth Woodville, queen consort of Edward IV) as an abridged audiobook early in the year and was disappointed. The abridged version showed little of the York court, concentrating on Elizabeth's times in sanctuary during the wars and Lancastrian restoration. It also expunged references to Edward's unfaithfulness, a thing that would have doubtless been sometimes on Elizabeth's mind, even if she tolerated it. However, skimming through the hardback book, I found that these elements were indeed there. I still wouldn't call it a favorite; I didn't connect with the portrayal of Elizabeth's personality. That said, Gregory should be commended for writing a decently sympathetic portrait of the woman who was - and in historical fiction (such as The Sunne in Splendour) still seems to be - the reviled Wallis Simpson of her age. As with her novel about Elizabeth's mother, Jacquetta of Luxembourg, Gregory portrays women as using forbidden herbalism and magic to gain their own form of power in a man's world.

The Red Queen

The extreme piety and sense of purpose that makes many readers dislike Gregory's characterization of Margaret Beaufort (grandmother of Henry VIII) at first enlisted my sympathy, reminding me of Dorothea Brooke in my beloved Middlemarch. However, eventually Margaret's self-centered outlook, and a rather slow-moving plot, turned me off. I only finished it to find out Gregory's unusual theory on the fate of the Princes in the Tower

The Kingmaker's Daughter

This novel - centering on the life of Anne Neville, queen consort of Richard III - was rather uneven. It had some wonderful moments showing the absolute horror and danger of childbirth in late Medieval times. Anne's relationship with her sister Isabel was depicted as close and complex. However, I never really felt like Anne's character was well defined. Especially confusing was how quickly she became loyal to her formerly-feared mother-in-law, Margaret d'Angou. Richard (yes, of course that's who we're really interested in) is quite well-drawn. Gregory doesn't come across as a raving Ricardian or a Shakespearean hater. Her Richard can be kind or ruthless, simultaneously charismatic and calculating.

While Gregory isn't a very highbrow author, I probably will pick up the other books in the series when I see them at the library. Of course I'm already raising my eyebrows at the premise of her new book on Princess Elizabeth of York. SPOILERS FOLLOW which appears to be that Elizabeth and Richard III were lovers. It is, of course, not an unprecedented idea and it's hardly surprising that it was the route Gregory chose to take. She is certainly never one to miss out on the most sensational interpretation.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)